The Internet of First Responder Things (IoFRT)

The "Internet of Things" or IoT is a common buzzword in the technology community these days. It refers to the increasingly prevalent distribution of sensors throughout the natural world, and the connection of those sensors – as well as other machines – to the Internet.

The "Internet of Things" or IoT is a common buzzword in the technology community these days. It refers to the increasingly prevalent distribution of sensors throughout the natural world, and the connection of those sensors – as well as other machines – to the Internet.

The running joke is that IoT is about putting your home refrigerator, thermostat, washer, dryer, microwave, range, TVs, computers, smart phones and even toasters on the Internet, or at least connecting them so they can talk to each other. Now what a toaster would say to a TV, or what the conversations between a washer and a dryer might include, could certainly make for a lot of talk show jokes and lists on a David Letterman show (should he return).

But clearly creating such an "Internet of Household Things" or IoHT would be quite useful. Take, for example, the urgent water crisis in California and throughout most of the West. If you could add sensors to every water fixture in the house, and then connect those sensors to computers and smartphones, you could determine where your water is being used and take steps to cut back use. Going one step further, if those water sensors also had valves, you could control your household water use from anywhere in the world. So when your teenager's shower has gone over five minutes in length, you could abruptly get a notification and then shut off the water (or turn on the cold water full blast) from your hotel room in Hong Kong.

How might this Internet of Things concept apply to First Responders – the paramedics and firefighters and police officers who respond to our 911 calls?

I recently had a twitter conversation about this with Ray Lehr, former fire chief in Baltimore, and former FirstNet State Point of Contact (SPOC) for Maryland. Ray suggested we should start talking about the Internet of Life Saving Things (IoLST) which I morphed into a possible Internet of First Responder Things (IoFRT).

There are many applications for the IoFRT, and I'd guess they fall into several buckets:

- First Responder Personal Things – the sensors and equipment which would be on or near a First Responder to help that officer do the job and keep the officer safe.

- 911 Caller and Victim Things – these sensors would help alert 911 centers and responders to problems so First Responders can quickly and accurately respond to calls for assistance.

- Information and Awareness Things – these sensors and machines would improve public safety by monitoring the natural and built environments.

"First Responder Personal Things" would include a variety of sensors and communication devices. Body worn video cameras – so much in the news recently after the events in Ferguson, Missouri – are one example of an IoFRT device. Most such cameras today record their video and hold it in the device. But if wirelessly connected to the Internet (by, say, FirstNet), a police commander, 911 center and other authorized users could see the video in real time to advise and support the officer.

A police officer's badge or other apparel might have a small radio which broadcasts a signal unique to that officer, which allows many other communication devices (smart phone, radio, tablet computer) to automatically recognize the officer and therefore allow access to restricted databases such as criminal history. A similar situation for a paramedic would allow her/him access to restricted patient files and healthcare history.

A police officer's weapon could have a sensor which only allows it to be fired if it is personal possession of the officer. Firefighters – especially those fighting long, sustained, wild fires, would have an array of sensors to monitor heart rate, respiration, ambient air quality, etc., alerting the firefighter and incident commander to firefighters who are overworked or in dangerous situations.

"911 Caller and Victim Things" would include those sensors on a victim or in their home or place of business which help to monitor and protect them. Medical sensors are an obvious application: people with a history of heart disease, stroke, diabetes or other conditions would have such sensors which would immediately alert them and their healthcare providers to impending problems. Such sensors might further alert 911 centers for dispatch of emergency medical technicians to an immediate problem.

Vulnerable people in high crime areas might have sensors or video cameras which could be activated at a moment's notice when they come into dangerous situations. Many homes and businesses are now equipped with video cameras, movement sensors and other sensors. A 911 call from the premise (or other activation by the owner) could give 911 centers and responding officer's immediate access to the telemetry and video from those cameras.

Finally, General Motor's OnStar gives us a premonition of the technology which will go into vehicles in the future. Vehicles which communicate with roads or automatically notify 911 centers after an accident, to include transmission of telemetry and video are definitely in the future.

"The Internet of Information and Awareness Things" is both more fascinating and frightening. Applications to support 911 response can be harnessed to many of these "things".

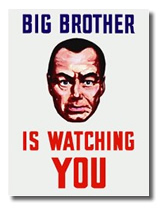

For example, Video surveillance cameras are becoming less expensive and more ubiquitous. Surveillance camera systems deployed by cities and counties receive significant scrutiny and attention from the ACLU and city/county councils such as the brouhaha surrounding Seattle's attempted deployment of a $5 million system. The use of unpiloted aerial vehicles with cameras is just starting deployment. But most such cameras are in the hands of businesses and private individuals, as demonstrated by the identification the Boston marathon bombers. Powerful new technology tools are becoming available for automated analysis of video, for examples automated license plate recognition, facial recognition and object recognition. We aid and abet this analysis by gleefully tagging faces in our Facebook photos, all of which Facebook uses to build its database of known faces. The largest license plate recognition databases are in private hands. In the near future every human being is likely to be recognized and tracked (and NOT by governments) whenever we are outside our own homes.

In the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the Department of Homeland Security was created. Fearing potential chemical, biological and nuclear terrorist attacks, it deployed a network of sniffers and sensors in cities and other potential targets. Similar technologies and networks could be deployed to support first responders.

For example, every load of hazardous material being transported by road, air or rail could be tagged and tracked. Every hazmat container stored in a building could also be identified and tracked, with firefighters watching them pop up on a tablet computer app when they respond to an event in the building.

We could even tag every can of spray paint or every cigarette lighter as the combination of those two items, plus a healthy dose of stupidity (which, alas, cannot yet be tagged) contributes to major home fires like this one.

It is now easy to imagine a world like that depicted by George Orwell in his novel 1984, where surveillance is both nefarious and ubiquitous, fueled by a government (probably controlled by private companies) out of control.

Like so many other choices faced by our early 21st Century society, the Internet of First Responder Things hold both great promise and some peril. Elected officials and chiefs of responder agencies will have many decisions to make over the next few years.

^ed

No comments:

Post a Comment